Caches - The unsung hero of CPU performance.

Computers are deeply integrated into almost every corner of our world. From data-centers beneath our oceans to satellites operating kilometers away in space. What enables this relevance is not just raw computational capablity, but its ability to store and efficiently access vast amounts of data in its memory. Computation, after all is only fast if it gets the data it needs and doesn’t have to wait for it. (This kind of explains why GPUs have boomed today, but more on that in another blog)

Let’s focus on the memory today.

Imagine you have a vast collection of books in your library and you need some of these for your work. Do you walk back and forth to retrieve each book?. No, right. You will collect all the books in advance and keep it on your “table” and then go through them. Once there, accessing them is immediate and efficient

Caches are the “tables” that CPU uses to fetch instructions and data after collecting it from a vast library known as its memory. Main memory is vast but slow to access. Fetching every instruction or data item from memory can stall the processor for hundreds of cycles. Caches sit close to the CPU cores, recently used and likely-to-be-used instruction/data that CPU needs. Rather than going to the memory, the CPU first looks into these caches for the data they need, often finding what it needs and avoiding expensive memory accesses.

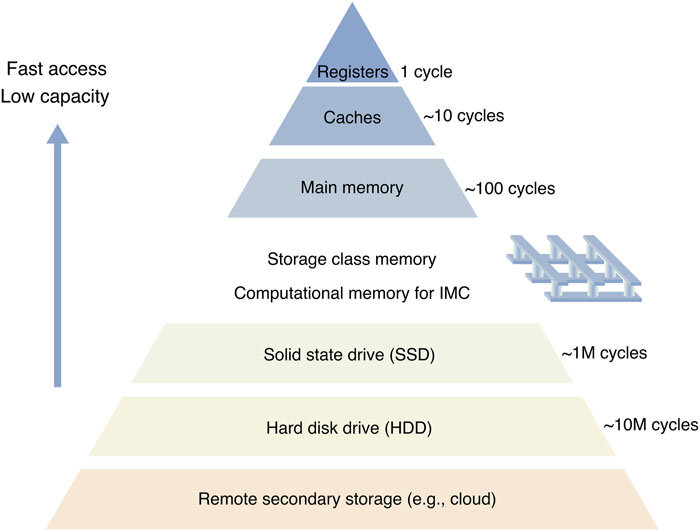

This fits into a broader structure known as the memory hierarchy, shown below.

Caches work because CPU programs exhibit Temporal locality as well as Spatial locality. Temporal locality means that recently accessed data is likely to be accessed again. Spatial locality means that nearby memory locations are likely to be accessed

Common questions regarding Caches

Now that we know what caches are, let’s tackle the four most common questions about Caches

Where can a block be placed in the Cache? (block placement)

There are some restrictions on where a block can be placed in caches and these create three main categories of cache organisation. These are:-

-

If each block has only one place it can appear in the cache, the cache is said to be direct mapped. The mapping for this is usually as follows -

(Block address) MOD (Number of blocks in cache) - If a block can place anywhere in the cache, the cache is said to be fully associative.

-

If a block can be placed in a restricted set of places in the cache , the cache is said to be set associative. A block is first mapped onto a set, and then the block can be placed anywhere within that set. The set is chosen by bit selection that is -

(Block Address) MOD (Number of sets in cache)if there are n blocks in the set, the cache placement is called n-way set associative

Direct mapped is simply one-way set associative, and fully associative cache with m blocks could be called “m-way set associative”.

The vast majority of processor caches today are direct mapped, two-way set associative, or four-way set associative.

How is a block found if it is in the Cache? (block identification)

Caches have an address tag on each frame that gives the block address. The tag of every cache block that might contain the desired information is checked to see if it matches block address received from the processor.

Now there needs to be a way to identify or know that the cache block does not have valid information stored in it. The most common procedure is to add a valid bit to the tag, indicating to say whether or not this entry contains a valid address or not. There cannot be a match if bit is not set

The memory address can be divided into three portions. The first division is between block address and the block offset. The block address can be further divided into the tag field and the index field.

The block offset field selects the desired data from the block, the index field selects the set, and the tag field is compared against it for a hit.

Which block should be replaced on a miss? (block replacement)

When a miss occurs, the cache controller must select a block to be replaced with the desired data. One benefit of directly mapped cache is that decisions are simplified - because there is no choice. Only one block frame is chosen, checked for the tag and only that block can be replaced. With fully associative or set associative placement, there are many blocks to choose from on a miss.

Naturally, there is a need to define a strategy to select which block to replace. Primary strategies include -

- Random - Blocks are randomly selected. Some systems pseudorandom block number to get reproducible behaviour, which is particularly useful in debugging

- Least Recently used (LRU) - To reduce the chance of throwing out information that will be needed soon, accesses to the blocks are recorded here. The block that will be replaced is the one that has been unused for the longest time

- First in, first out - As LRU can be complicated to calculate, this method approximates LRU by removing oldest block inserted rather than removing least recently used

What happens on a write? (write strategy)

Reads dominate processor cache accesses. All instruction accesses are reads and most instructions don’t write to memory. The block can be read from the cache at the same time that the tag is read and compared, so block read starts as soon as address is available. If it is a hit, requested part is passed on and if it is a miss, there is no benefit, just ignore the read value.

However, write can use this strategy. Modifying a block cannot begin until the tag is check to see if the address is a hit or miss. Because tag checking cannot occur in parallel, writes normally take longer than reads.

Another complexity a processor introduces by specifying the size of the write, usually between 1 to 8 bytes. Doing this constrains the write to change only that portion of a block.So a read can access more bytes than necessary faster and without fear.

Cache designs are often distinguished by write policies and there are two basic options :-

- Write-through - The information is written to both the block in the cache and to the block in the lower levels of memory hierarchy

- Write-back - The informations is written only to the block in the cache

To reduce the frequency of writing back blocks on replacement, a feature called the dirty bit is commonly used. This bit indicates whether the block is dirty i.e modified while in the cache or clean i.e not modified. If it is clean, the block is not written back on a miss, since same data is found in lower levels.

Both write-back and write-through have their advantages.

With write-back, writes occur at speed of the cache memory, and multiple writes within a block require only one write to the lower-level memory. Since some writes don’t go to the memory , write-back uses less memory bandwidth making write-back attractive in multiprocessors. Since write-back uses the rest of the memory hierarchy and memory interconnect less than write-through, it also saves power, making it attractive for embedded applications

On the other hand, Write-through is easier to implement than write-back. The cache will always remain clean. Write-through also has the advantage that the next lower level has the most current copy of the data, simplifying data coherency

How Cache performance is calculated?

A better measure of memory hierarchy performance is the average memory access time :

Average memory access time = Hit time + Miss rate x Miss penalty

where hit time is the time to hit in the cache, Miss rate is (misses / total requests) and Miss Penalty is the time to fetch data from main memory when there is a miss

The components of average access time can be measured either in absolute time - say, 0.25 to 1.0 nanoseconds on a hit or in the number of clock cycles that the processor waits for the memory - such as a miss penalty of 150 to 200 clock cycles. Average memory access time is still an indirect measure of performance, although it is a better measure than just miss rate, it can’t be a substitute for execution time.

Basic Cache optimizations

The average memory access time formula given above gave a framework to present optimization for improving overall performance of cache. So we can categorize optimization into following categories:

- Reducing the miss rate - larger block size, larger cache size, and higher associativity to reduce miss rate.

- Reducing the miss penalty - multilevel caches and giving reads priority over writes.

- Reducing the time to hit in the cache - avoiding address translation when indexing the cache.

While most of these principles have remained unchanged for many years, modern workloads especially the irregular and data-intensive ones continue to challenge the effectiveness and need for better caching, motivating ongoing research in prefetching, coherence and adaptive cache policies for these type of workloads.

Thank you for reading!!

The content of this blog is referenced from Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach (5th edition) by John L. Hennessy and David A. Patterson. If you are curious to know more about caches, I highly recommend to read this book to satisfy your curiosity.

Also if I have missed anything or if you have any thoughts to share, feel free to contact me:)